|

| from Clocks Magazine, Sepember 2004 |

English Wall Clocks, Part 1 of 7by Ian Beilby, UKDownload a pdf of this article English wall clocks have evolved over a period of nearly 300 years. Their appeal and longevity is without doubt due to their visual accessibility and excellent timekeeping qualities. There can be little doubt that a wall clock has much to commend it. It takes up very little space, is out of harm’s way and (if suitably placed) is visually accessible even in a crowded room. All these factors contributed to wall clocks being used in both domestic and public buildings where people needed to know the time. In this series of short articles I want to take a look at a range of clocks that chart the history and development of the English wall clock from the 18th to the 20th century. We will take a look at both 18th and 19th century spring-driven wall clocks and the more flamboyant and decorative weight-driven tavern and Norwich clocks that played a parallel role in the development of the English wall clock. The first English wall clocks to be introduced in the 1700s were the small and elaborately carved cartel clocks. A good example in scarce original condition is shown in figure 1. This clock was made in London by John Bennett and dates from the first half of the 18th century. There are several John Bennett’s recorded as working in London during the early part of the 18th century and so it is impossible to attribute this clock to a specific maker. Needless to say the clock is an early example from around 1730. The cases were often asymmetric in design and carved from wood in highly flamboyant forms. The case designs would frequently incorporate eagles, cornucopia, seashells and other baroque devices.

On this clock the brass and silvered dial displays a ‘false pendulum’ aperture, a common feature on early 18th century cartel, wall and bracket clocks. The movement and dial were both fitted into the case from the back. A brass strap was attached to the movement plates and then screwed to the back of the case. The movement plates on early cartel clocks were of a slim rectangular design. The lavishly carved cases of the early cartel clock were not however to everyone’s taste (and pocket!) and eventually the cases became much less flamboyant, ultimately evolving into the much simpler English dial clock. The relatively short life of the cartel clock makes them quite rare and they are usually only now encountered in private collections and rarely appear on the open market. These were purely domestic clocks, and as you would expect they were made to complement the highly decorative furniture of the period. The cases were carved from wood and then gilded. The brass dials were usually engraved and silvered, normally around 8in in diameter. The cartel clock had a spring driven fusee movement and verge escapement. Although the anchor escapement had been invented in the late 17th century, the verge movement was used in spring-driven wall clocks up until around the 1800s. The verge escapement although reliable was not very accurate and it was not until the wholesale adoption of the recoil anchor escapement in the early 19th century that accurate timekeeping was achieved and the large-scale production of English wall clocks as we now know them commenced. The first truly distinctive English wall clocks appeared around the 1770s and were much simpler than the cartel clock in both construction and design. Figure 2 shows a very good example of a London wall clock c1790 by William Dorrell, again in rare original condition. William Dorrell was born into a well-respected London clockmaking family. His grandfather, Francis was apprenticed in 1693 and became a free clockmaker and member of the Clockmakers Company from 1702 to 1755. His son, another Francis, likewise was apprenticed in 1731 and became free, working as a clockmaker in Whitecross Street from 1755 to1780. William is recorded as working in St Martin-in-the-Fields and Bridgewater Square. William was apprenticed in 1768 and recorded as free and a member of the Clockmakers Company in his own right from 1784 to 1810.

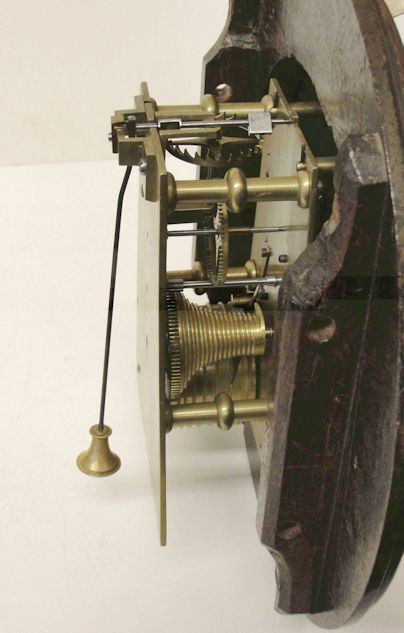

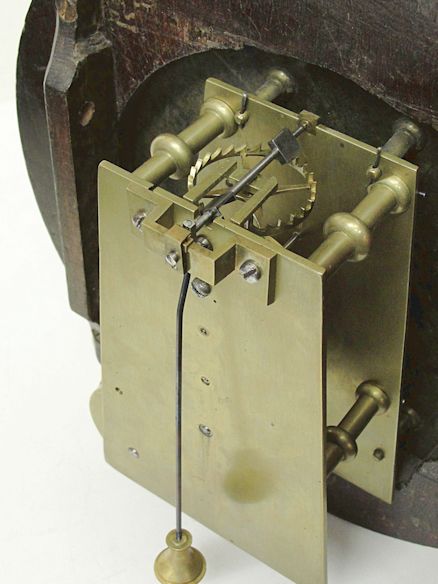

The dial of this clock is similar to those used on the cartel clocks but the case is clearly not as ornate and far less elaborate. The 8in dial with its narrow wooden dial surround takes precedence over the case. It was these clocks which became the forerunner of the English wall clock, as we know it today. The oak case is of simple ‘salt-box’ design. The dial, movement and dial surround fit directly to the case and are held in place with wooden pegs. The backboard of the case was usually extended above and below the case, often, as here, with a simple shaped outline. Early wall clocks can be found with wooden bezels, however this slightly later clock is fitted with a cast concave section brass bezel. With its silvered dial and original fancy steel hands this clock is a good example of a late 18th century English wall clock. The full outside Arabic numerals recording the minutes and Roman numerals recording the hours are again typical features of this period. Ornately written maker’s signatures are also characteristic of the 18th century and frequently found engraved on clock dials at this time. By the late 18th century the false pendulum apertures often found on earlier dials were being replaced with the maker's signature. A close-up of the verge movement is shown in figures 3 and 4. These movements were fitted with a fusee and short integral pendulum. In figures 3 and 4 you can clearly see the verge crown wheel at the top of the movement, the fusee with its spiral grooves and the short pendulum. The plates on this wall clock are rectangular, however many early movement plates were tapered or were made with decorative ‘shoulders’ at the top of the plates. These clocks, and many others like it, were to be the start of what was to become a long and successful enterprise for English clockmakers. Combined with longcase clocks, they were to typify the output of the English clockmaker for nearly 300 years. In the next part of this series of articles on English wall clocks we look at two interesting tavern clocks, another 18th century design of wall clock only of slightly different proportions Acknowledgement Both of the clocks shown here form part of a private collection and I would like to sincerely thank the owner for permission to photograph and include these clocks in this article. Download a pdf of this article |

| © 1977 to 2015 Clocks Magazine & Splat Publishing Ltd |