|

| from Clocks Magazine, August 2011 |

Clock dial curiositiesby M F Tennant, UKDownload a pdf of this article Although the majority of my work as a dial restorer is with painted dials, I have recorded some interesting brass dials or pieces thereof. In the days when my husband dealt with brass-dialled clocks, we photographed nearly every dial. Other clock repairers would frequently send me painted moons, break-arches or automata that needed attention. All too often I never knew what the main dial looked like or even the name of the clockmaker. Brass was expensive in the 18th and 19th centuries. The use of scrap brass was common. Trial bits of engraving sometimes turned up on the back of a chapter ring, complete with mistakes and miss-spellings, though spelling was not standardised for quite a long time. Unlike the painted dial, mistakes in engraving could not be rectified. Occasionally some real errors did turn up. The back of a dial is often interesting with repairers’ scratch marks giving the date and possible name or initials. Then there is the evidence of alterations that may not be visible on the dial face. One brass date dial belonging to a square eight-day dial made by Edmund Davies of Ellesmere, No 598 (1781-1798) really was unusual, figure 1. Once cleaned up, it was easy to see ‘John Ebsworth in New Cheap Side Londini Fecit’ on the back of the dial. There were also some nice tulips and fruit engraved in a circle. Ebsworth was apprenticed in 1657 to Richard Hymes and presumably worked on his own from 1665 until his death in 1669. There was also a possible brother, Christopher, working in 1670 who may have worked with John earlier. How this piece of London engraving turned up in Ellesmere, Shropshire, nearly two centuries later is open to conjecture. After about the middle of the 18th century, depending on location, painting began to feature on brass clock dials. The most common was a painted moon dial, but as the century progressed, painted break-arches began to appear. These sometimes had moving parts such as a rocking ship or other automata. Bracket clocks tended to follow the styles of the longcase clock, though the work was, of course, much smaller.

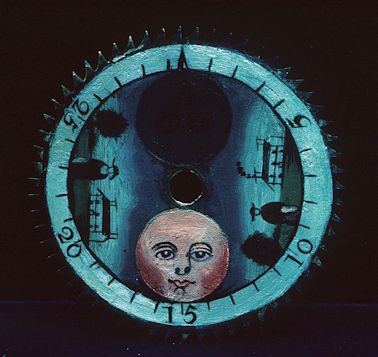

An interesting example of a c1770, figure 2, country-made bracket clock had a rocking ship automaton in the break-arch. This was sent to me without any clockmaker’s name, just the painted parts for restoration. The painting could be called crude, but interesting. Painted break-arches were often left unvarnished after painting had dried, so all the dirt and grease would eventually stick to the paint. Other examples were varnished, which protected the painting. On removal of the dirty discoloured varnish, the true colours could be seen. In this case, varnish had been used so no actual re-painting had to be done. The rocking ship automaton was made of thin brass. In those days it was not realised that oil paint would often not stick to brass. For new work, I use a special primer for brass. Frequently, these moving parts have shed a lot of paint. A very early rocking ship was seen where originally the brass was engraved and then a bit later on painted. This paint was dry and flaking, which exposed the engraving in some places. These dial painters were usually anonymous, but one rare example turned up on a bracket clock made by Robert Ward of London c1770, figure 3. The signature ‘Wm Grimaldi’ is in the lower right hand corner, but very indistinct. Grimaldi was a well-known London painter and his signature shows his Italian origins. The painting is of far better quality than the previous example, with an extraordinary arch on the right. It was not unknown for a London artist to do clock painting and Zoffany (1733-1810) was one of these. Another anonymous northern longcase clock dial had a very amusing revolving painted insert, figure 4. The painting of a hunter with his gun and dogs chasing a fox is very naive. It was probably made in the 1770s, but again no clockmakers’ name or any indication as to what powered the dial to revolve. Later, painted dials occasionally had a small ‘days of the week’ dial incorporated in the main dial. This had no teeth and was moved on manually.

A far more elegant example of a brass dial with an interesting insert, figure 5, was made by Jason Cox of Long Acre, London, 1723-1751. Even the engraving of the placename at the bottom of the dial is unusual. In order to get ‘Long Acre’ into the space between V and VI, the letter ‘e’ was put very small above ‘Acr’. The insert with the days of the week, figure 6, has various personages with their attendant days. Sunday has rays around his head and carries a bow and arrow as well as a lyre. Monday looks more like a warrior, possibly Roman. Tuesday shows another warrior of the same type. Wednesday is the god Mercury, complete with wings on his heels and helmet. Thursday sports a crown, but holds a shaped staff in one hand with a bird on top, while the other hand clutches what might be a thunderbolt. This may refer to the god, Thor. There is also a bird at his feet. ‘Fryday’ is definitely female, holding a heart and some flowers, while a small cupid is by her feet. Saturday is represented by Father Time. Moon dials are really a special subject on their own. Many beautiful examples exist, but it is the amusing and unusual ones that are often overlooked. The earliest moon dials were engraved and silvered, sometimes with the starry sky left silver, but others had the sky painted dark blue with gold stars. Although this type of moon dial was made in London, as early as c1720, in America the style persisted far longer, figure 7. This moon dial was made for Thomas Harland of Norwich, Connecticut, 1773-1809. The engraving of the moon face is certainly peculiar, with either a beard or a pronounced five o’clock shadow. The state of the paint on the blue sky is not good.

Moon dials, especially in the north west of England, gave local artists a chance to express themselves at various levels of expertise. Some were very crude indeed, figure 8. This one is shown in its unrestored state. There is an almost invisible black faced moon opposite the other moon. Painting is almost childish and the numerals were not very well done. The northern clockmaker is unknown. In some cases where the painting was considered to be so bad someone ‘improved’ the situation. This could be by over-painting or in one case, a printed picture of a moon dial was stuck on to the original and then heavily varnished. Southern clockmakers also used painted moons, figure 9. Here the clockmaker, Samuel Whitchurch of Kingswood near Bristol, used one of the saddest moon faces ever seen, figure 10. Somewhere there exists an almost identical Bristol-made moon dial with the same lugubrious expression. The age-of-the-moon and tidal markings were a separate piece of engraved and silvered brass in the break-arch. Engraving in the half hemispheres probably depicting sunrise and sunset is quite good. The engraved dial centre may have been originally silvered but it was decided to leave it brass. This has not shown up well in the photograph.

Local clocks in my area (Wrexham and Chester) are always interesting. The one shown in figure 11 was made by Thomas Hampson of Wrexham, 1718-1754. The clock was numbered 1018, but this does not give an exact date, as his sequence of numbering was not understood. The waking and sleeping primitive faces in the half hemispheres are amusing. Hampson must have had a sense of humour as one of his dials had ‘Tempus Fugit’ on the arch and below that was a round boss engraved with Father Time chasing a large fly. The use of an improving or religious motto on the break-arch was common. ‘Time Shows The Way of Life’s Decay’ was on this dial. Corner spandrels represent the four seasons, but it is the moon dial that is really interesting, figure 12. Instead of a dark blue sky, this moon dial has a much paler blue sky that seemed to be popular in the Wrexham area. Moon faces are simplistic to say the least, but they do have a rather amused expression.

Another much later Wrexham clock was made in a very different style, figure 13. John Jones of Wrexham, 1778-1782, was the clockmaker and the half hemispheres are engraved with rather sketchy maps of the world. Where the date hand would have been attached, an extra winding hole was added for a musical train. This was done in Victorian times and unfortunately a gong was also put in to replace the bell. Quite a few clocks have suffered these ‘improvements’; however, it is the moon dial, figure 14, that is really interesting. This has the same sort of pale blue starry sky as the Hampson clock, but originally the age of the moon had been painted on a white background around the periphery of the moon dial. Then instructions must have been changed and the sky continued to be painted over the white area. This shows up as a paler band, but is definitely original. Paint can get thinner with age, so what might have been invisible at the time of manufacture now shows up well. The age of the moon was a separate silvered and engraved ring in the break-arch. Two comets were also painted in the sky, which was quite usual at that time and can be seen on some Liverpool clocks. The case of this Jones clock, figure 15, was very elaborate and heavy, being solid mahogany. It does not look as if it were locally made.

Automata in longcase brass dials were expensive, but the standard of painting in the arch could be quite crude, figure 16. This clock was made by John Stanyer of Chester, c1790. The break-arch has Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden painted on it. As it was originally never varnished the painting looks very dark due to all the dirt. The main dial should have been silvered, but the owner refused to have this done. However, after cleaning, the painting, figure 17, showed up much more of this naive Garden of Eden. Adam and Eve are modestly covered with long hair. The brass corkscrew serpent revolves endlessly around the apple tree, while two horses graze in the distance. The motto on the arch is suitably pious but ‘except’ seems to replace ‘accept’. The movement, figure 18, seemed to be interesting enough to photograph after cleaning. Both figures have moving arms and as mentioned before, the serpent revolves around the tree trunk. Not all automata painting were as crude as this example, but it is interesting to see what was considered acceptable in those days on a pretty expensive clock, although this is definitely provincial work. These examples of clock dials, parts of dials and moon dials have been selected from a collection dating back over 30 years of work that has come in for restoration. Most of them would never have been illustrated in any book, but they are still interesting and in some cases quite comical. References Figure 7 courtesy of the American Watch and Clock Museum, Bristol, Connecticut. Figure 9 courtesy of the National Trust. Figure 11 courtesy of Wrexham Heritage Centre. Download a pdf of this article |

| © 1977 to 2015 Clocks Magazine & Splat Publishing Ltd |