|

| from Clocks Magazine, Sepember 2004 |

The artistry of the skeleton watchby Douglas Caulkins, USADownload a pdf of this article Even when arranged with other timepieces, skeleton clocks and watches always draw attention. Instead of a handsome case or a beautiful dial the focus of a skeleton watch or clock is the intricate and artful piercing of the plates to display functioning of the movement. To illustrate this point a watch dealer friend often displayed a New England Watch Company skeleton watch, along with his other pocket watches, in the window of his shop. He said that many potential customers came into his shop to inquire about the unusual watch. Despite the relatively large number and variety of skeleton clocks that were produced by British clockmakers, English skeleton watches are a rarity and are seldom offered for sale. It took many years and some frustrating misses to add the watch illustrated in figure 1 to my collection. The photograph shows the white enamel dial with Roman numerals and nicely pierced gold arrow hands. As can be seen, the winding arbor is located in the hole in the dial next to the number four. The display case is engraved and made of low carat gold with a stirrup-shaped bow attached to a tall pendant. A high dome crystal covers the dial and a bull’s eye crystal covers the movement. The watch rests on the pontil of the crystal keeping it vertical in the dial-up position. In figure 2 the intricately pierced and engraved movement can be seen. The top plate is cut away and engraved in a floral pattern that includes flower rosettes, stems and leaves. The table of the single footed balance cock is pierced in the form of a flower including the stem and leaves, while the diamond cap jewel is located in the centre of the flower surrounded by the petals. The fast/slow indicator is located in the pierced foot of the balance cock. The signature ‘A Tyler, London 371’ is engraved on banners extending from either side of the balance cock foot. Even the mainspring can be seen through the cut-away and engraved cap of the main spring barrel. The movement is so cleverly skeletonised that the verge escapement can be easily seen through the high domed crystal covering the movement. The fusee-compensated verge movement with a continuous screw set up to the mainspring, baluster shaped pillars and a pierced and spreading balance cock foot would indicate the watch was made in the last half of the 18th century. I could find no reference to A Tyler, London, either in Watchmakers & Clockmakers of the World Volume 1 by G H Baillie or in Volume 2 by Brian Loomes. Philip Priestley, a friend and researcher, checked his extensive references to no avail. When I found an almost identical watch illustrated in The Camerer Cuss Book of Antique Watches the author describes it as ‘likely to be of Swiss origin’ even though Robert Slater, the maker of this particular watch, is listed in Baillie. The three skeleton watches pictured in The Artistry of the English Watch by Cedric Jagger are more completely cut away and therefore lacking some of the decorative piercing and engraving that are found on the Tyler watch in figure 2. This form of movement decoration seems to be confined to the late 18th century, therefore they are considered to be rare.

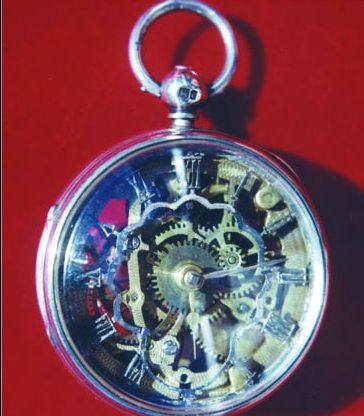

Are these interesting horological curiosities English or Swiss? Certainly at this time the Swiss were taking unfair advantage of the excellent reputation held by the British watchmakers, signing them with English sounding names such as Tarts and Samson. They made watches in the English style with the exception that most have double-footed balance cocks. Looking through auction catalogues I have seen several Swiss or possibly French skeleton watches and they vary considerably from the English style. Most have a pierced decorative overlay that is mounted with paste or semi-precious jewels over the movement and many also have pierced and engraved filigree plates surrounding the dial. In an April 2000 Antiquorum auction catalogue I found a Swiss watch in which the movement is cut away and decorated in a very similar manner as the illustrated A Tyler example with the exception that the Swiss watch is housed in a 20-carat case. The Tyler watch is still an enigma to me: the fast/slow regulator is located at the base of the table of the balance cock which seems to be typical of the examples signed with the names of British makers. On the Swiss watch the fast/slow regulator is located on the top plate of the movement. I must admit that I still cannot make up my mind about this watch that certainly leaves open the possibility there may be a Swiss skeleton included in my British collection. Were these watches skeletonised to reveal the complicated and precise operation of the mechanism or were they made to demonstrate the skill of the watchmaker? The watch in figures 3 and 4 is a partial answer to this question. It is a much larger18th century verge watch that is completely skeletonised with similar flower rosette and engraving as found on the Tyler watch. It is housed in a silver 19th century display case. This early 19th century movement was skilfully cut away and engraved by a talented watchmaker. This is a time consuming and difficult process. As can be seen the plates are precisely cut away to reveal the escapement and the rest of the movement. There is the real danger that if too much of the plate is removed that they could bend when the watch was assembled and the mainspring wound. One only can imagine the time that was invested with jewellers saw to cut away a thin silver dial to the very pleasing arcaded design seen on the watch. The watch even has an unusual balance cock with a profile of an officer engraved at the base of the table. The watchmaker took pride in his work and signed it ‘Fred W Jensen, NY’. When I looked in American Clockmakers & Watchmakers by Sonya L and Thomas J Spittler and Chris H. Bailey I found a reference to a Fred Jensen who had a clock museum and store in New York City. I think it safe to assume that this watch was one of the exhibits. I have seen several other examples. A few were prominently displayed in the window of the watchmaker’s shop to demonstrate his skill. It was always worthwhile to ask to see the watch and hear the pride in the voice of the craftsman who made it as he described the features of his watch.

The last example, illustrated in figures 5 and 6 was made by a very creative watchmaker and a personal friend, Jesse Cannon. Jesse especially enjoyed challenging restorations of complicated watches such as minute repeaters and pocket chronometers. One of his most unusual restorations was a watch that was found with other artifacts that were recovered from a sunken paddle wheel river boat that had been under water for more than 100 years. The watch was restored to running condition and is now on display with other artefacts from this ship in a museum. He shared with me the process he went through in selecting the movement to be skeletonised and the time-consuming task of cutting the plates away. He found it to be particularly arduous to cut almost completely away with jewellers saw the thin gold dial leaving only the Roman numerals. He then carefully polished the exposed steel surfaces and gilded the brass ones. The watch is so completely skeletonised that when it is held to the light essentially what is seen are the wheels and not the plates that support them. After showing the watch to friends and collectors he quickly lost interest in it. The joy to Jesse was the challenge of making it therefore he was pleased when I asked him if I could add it to my collection. There seems to be a renewed interest in skeletonised pocket and wristwatches. They range in price from a few pounds to $122,900.00 paid for a Breguet tourbillon wristwatch. Download a pdf of this article |

| © 1977 to 2015 Clocks Magazine & Splat Publishing Ltd |